Hi there. I’m grateful for you.

This is the third installment of a three-part reported story, “Sharks’ Mouths: A Political Landscape Long Feared by Immigration Advocates,” developed in conversation with a humanitarian aid volunteer at the US/Mexico border. Her name and identifying details, along with those whose stories she’s connected me to, have been changed for their protection. Read part I, “Fear and Confusion, Tamales and Kings,” and part II, “Two Truths and So Many Lies.”

Can you imagine being told you may need to stop attending your place of worship, indefinitely, because doing so is no longer safe? Getting notice your green card (formerly permanent resident card), the very document that ensured you were at last secure in your new home country, could be revoked? Living in terror that masked men and women claiming to be government agents might grab you or a loved one from the street, a job site, your home, even a hospital or church? That you and your kids might be rounded up in a raid involving pepper spray and rubber bullets and other forms of state-violence? Since the posting of part II last week, footage of raids and detainments is easy to find, some Catholic bishops have taken the rare step of excusing the faithful from celebrating Mass for their safety, and US immigration officials have announced that “lawful permanent residents found to be in violation of immigration laws could lose their legal status and face deportation.”1

Today, the braid of spurn and welcome at the US border that’s led to this moment and two families who’ve migrated to the United States and are intimately familiar with each strand of that braid. Both are living in fear. Thank you for not turning away. Thank you for witnessing with me. Plus, scroll to the end for some specific, actionable steps to take if we’re not OK with what’s being done in our names from a longtime immigration advocate and the author of the book being called “a primer text on the issue of immigration.”

A history of answering the wrong question—on repeat

“Lisa” (a humanitarian aid volunteer at the US/Mexico border) met “Elena” a few years back in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico, a border town that abuts Brownsville, Texas, United States. She would later serve as translator during therapy sessions for the mother of three. By then, Elena had been kidnapped and gang-raped, her two toddlers held at her side. She’d been abducted while awaiting her scheduled asylum hearing with US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) in a Matamoros encampment. “She was deeply traumatized, deeply wounded,” Lisa recalls, trailing off as if transported, as if once again searching for the words to lay bare days that played out like a nightmare.

Despite “Prevention by Deterrence,” a 1994 Clinton administration policy aimed at making migrants crossing the Sonoran Desert suffer so badly they’d stop coming, people had continued coming. More than 6 million since 2000 had attempted to navigate the Sonoran Desert to get to the US border by 2014, per a Human Rights Watch Report. And the unauthorized population inside the United States had doubled by 2014. By 2018, numbers at the border had skyrocketed.2 So the first Trump administration doubled down on an old question: How can we increase suffering?

Elena and her family were caught in the crosshairs of one answer by that administration, “Migrant Protection Protocols” (MPP). The policy, known as “Stay in Mexico,” changed the customary practice of allowing asylum seekers who’d been granted hearings to await appointments in the United States with family.

Eventually, 70,000 people were sent to wait in Mexico, bottlenecking Mexican border towns. Massive encampments, rampant with gang and cartel activity, mushroomed in major crossing spots. Those seeking safety became sitting targets, not just for victimization on the spot but also for exploitation of family members in “El Norte.”3

Elena’s husband and eldest son crossed into Brownsville from Matamoros just before MPP’s rollout. And though Elena planned to follow shortly, the policy forced her to remain alone with two young children as the encampment bulged.

Had the administration asked why so many people were flocking to the border, the answers would have been clear. Multiple sources point to climate change, poverty, and violence. But the tradition of avoiding this question dates back before “Deterrence.” The Reagan administration conducted mass deportations without due process, when, between 1981 and 1990, nearly a million Central Americans came to the southern border. Their why? An era of “Dirty Wars” that tore apart those countries, leaving many destitute and terrorized—wars rife with US involvement.4

MPP wasn’t 2018’s first answer to the wrong question. Rather, Stay in Mexico followed a policy that was quickly repealed by court mandate, but not before reaching its goal of inflicting suffering. Zero Tolerance, announced in April 2018, had ensured that all who came to the border—whether through ports or between them—were treated as criminals. All encounters were classed as “apprehensions.” People picked up in sweeps, people who crossed into the United States and walked miles to present themselves at guard stations, and people who entered legally through ports were all “apprehended” and pressed into one of two pipelines: Adults were placed in five-point shackles and imprisoned or deported. Their children were stripped from them and held in makeshift “detention centers,” often manned by people untrained in working with children and often in abandoned strip malls across the country, miles from where they entered.5

Those actions were taken at the border, largely hidden. The current Trump administration is conducting apprehensions out in the open, in US cities—during routine traffic stops, at job sites, and even in and around hospitals and churches. Now, the question remains the same. Only the suffering is being aimed not just at people attempting to migrate to the United States but, also, at people who have already been living in the country, many for decades, many with no criminal histories.

A raid last week near my last brick-and-mortar home in Southern California left one farmworker dead (chased to his death when he fell 30 feet, according to his niece) and many critically injured. Men in tactical gear—US Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents—most masked, blocked the road near the targeted farm and then fired projectiles into the crowd that had gathered in protest, throwing canisters that emitted yellow or white gas throughout the afternoon. First responders declared a mass casualty incident for the injured. Photos show people of all ages in the crowds. Those injured included a 60+-year-old woman, gassed and hit by a projectile. Some 200 were detained. US citizen workers caught up in the raid told reporters they were held for hours, released only after deleting photos and videos of the raid from their phones under force.6 I spent the morning searching images for familiar faces.

This is no doubt only the beginning. With the July Fourth passage of the Trump administration’s massive domestic policy bill, the government plans to spend $45 billion to build immigration detention centers, around $30 billion to hire more ICE personnel, and $14 billion for deportation operations.7

Back in 2018, no agency maintained records of the whereabouts of who was taken or deported where when families were split. This became clear when the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) won its challenge of family separation. In Ms. L v. ICE, US District Judge Dana M. Sabraw ordered the reunification of families by July 2018. No one knew how to make that happen.8

When Lisa heard about an organization called Each Step Home working to figure it out, she was in. One step was to connect separated children with their US extended families. Lisa served as an intermediary for those families. Many had tenuous legal status of their own and little by way of English language skills or extra funds. And, Lisa recalls, the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) threw obstacle after obstacle in their way.

A parallel history of welcome and defiance

Lisa tells me she’s just heard from a friend, “Camila.” She wants to send me a photo taken at Camila’s son’s high school graduation. I can hear the smile in Lisa’s voice. But I sense a tentativeness behind her warmth I can’t place at first.

Then she tells me a story, asking at the end, “Can you even imagine that choice?”

I can’t. I don’t want to. She’s just described a decision Camila faced, back when she, like Elena, was stuck in Matamoros as encampment conditions worsened. And I, at first, chalk the hint of forlornness in Lisa’s tone up to this.

Though Camila had no family in the States, when she realized she couldn’t protect herself or her son, “Carlos,” from the violence in her home country, Honduras, the pair made the arduous journey to the US border. Never as they traveled did she imagine that, so close to a new start, she’d face yet another threat she couldn’t match: The longer they waited, the greater the risk the cartel would “recruit” Carlos, a young teen, forcing him to work for them.

Camila fretted. She imagined her boy forced to run drugs—or worse. She prayed. She begged God to provide any other answer than the one that would tear her in two. At last, she knew what she had to do. She took Carlos to the bridge at the port that connected Mexico with the United States. And she watched him cross to the other side alone, pleading that her broken heart would be her son’s salvation.

Camila wasn’t alone in this decision. Because unaccompanied minors weren’t deported at the time, parents had started sending kids into the United States alone as the dangers of encampment life increased, beseeching whatever deity they believed in to help their children find safety, if not human kindness, alone in a new country. There was the 4-year-old Lisa saw on the bridge, cradling an infant sibling. There was Carlos. And there were many others.

At first, only parents with family in the United States sent their children on their own, hoping ORR would connect the families quickly. But as the dangers became untenable, unaccompanied minors crossed with or without loved ones on the other side.

Carlos, Lisa recalls with pride, was the first unaccompanied minor Each Step Home connected with an independent sponsor, a family willing to take him in.

The changing situation once again guided Lisa. With the growing number of migrant children in the United States alone, she joined Al Otro Lado (The Other Side), a legal organization based in San Diego / Tijuana, helping parents with kids alone in US custody qualify for humanitarian parole.

At that time, humanitarian parole was supposedly granted only to those whose situations met a narrowly defined criteria, Lisa explains. In fact, agents weren’t checking. Meeting the quota at each port of entry was, instead, the sole consideration.

For the next two years, Lisa worked to parole parents into the United States. Once they were here, she helped them locate and then get custody of their children.

“Can you even imagine that choice?” Lisa asks. I can’t. I don’t want to. She’s just described a decision Camila faced back when she, like Elena, was stuck in Matamoros as encampment conditions worsened.

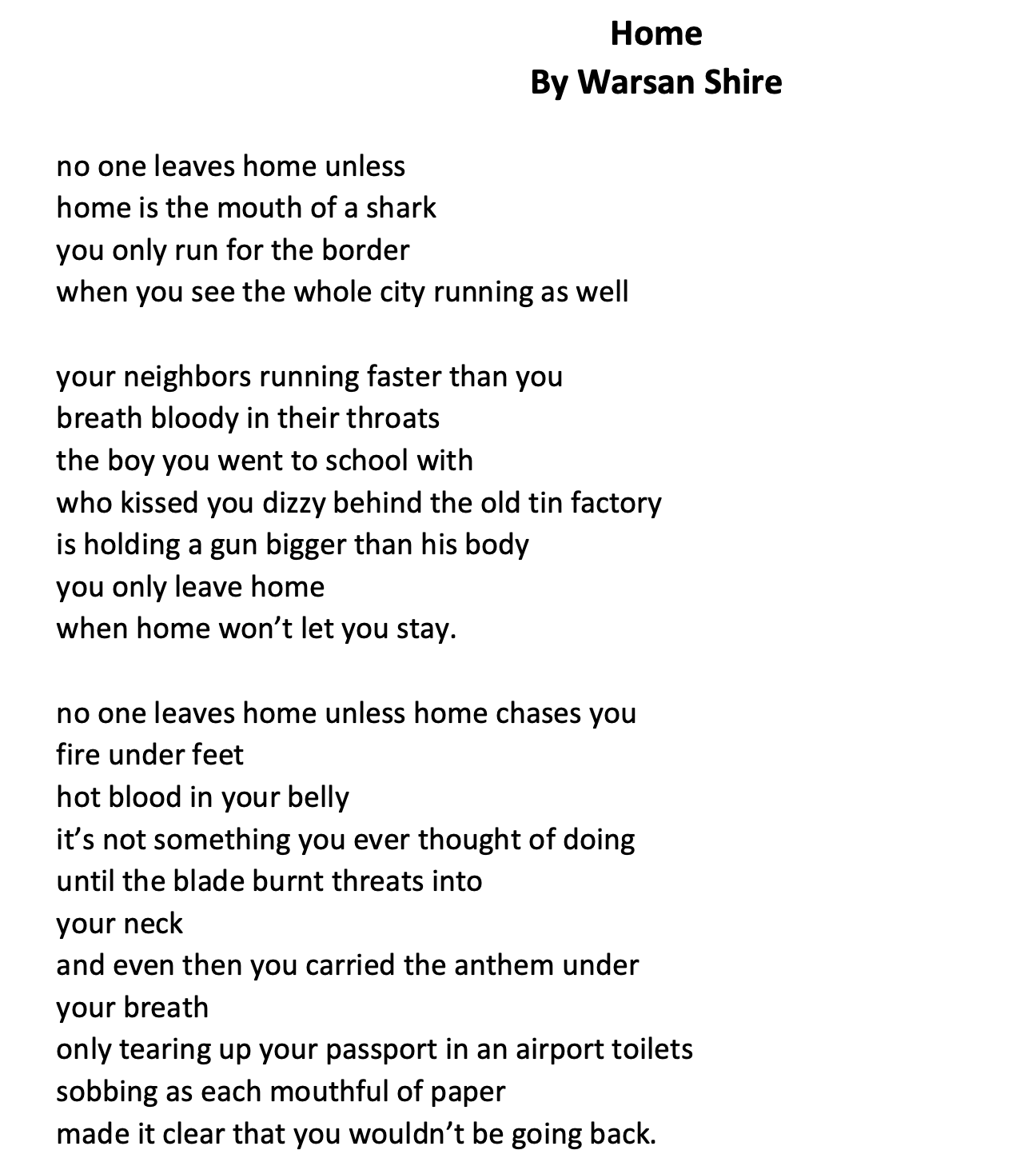

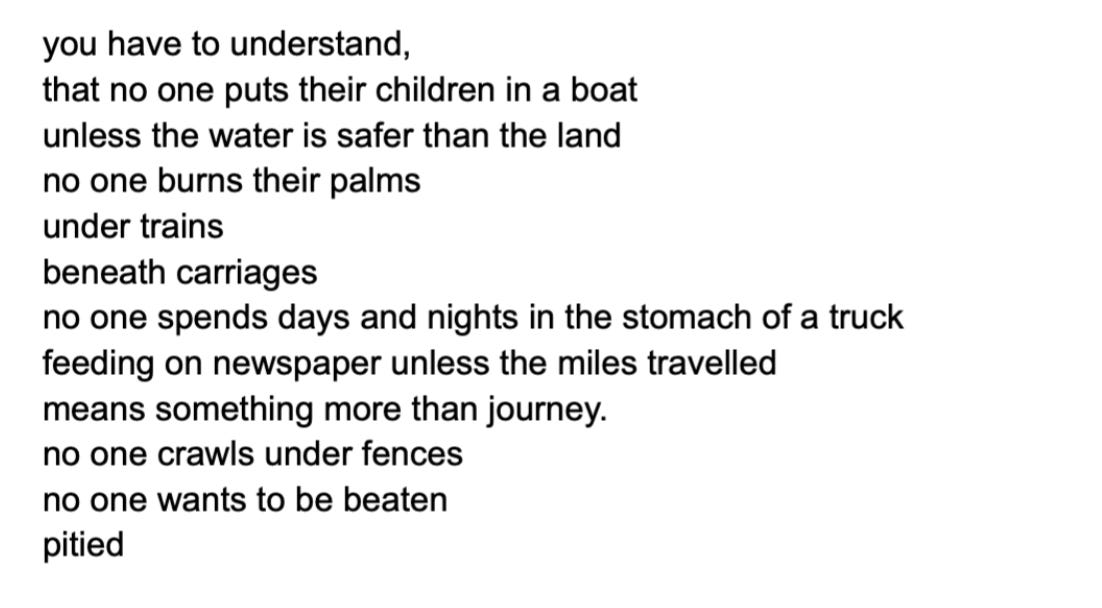

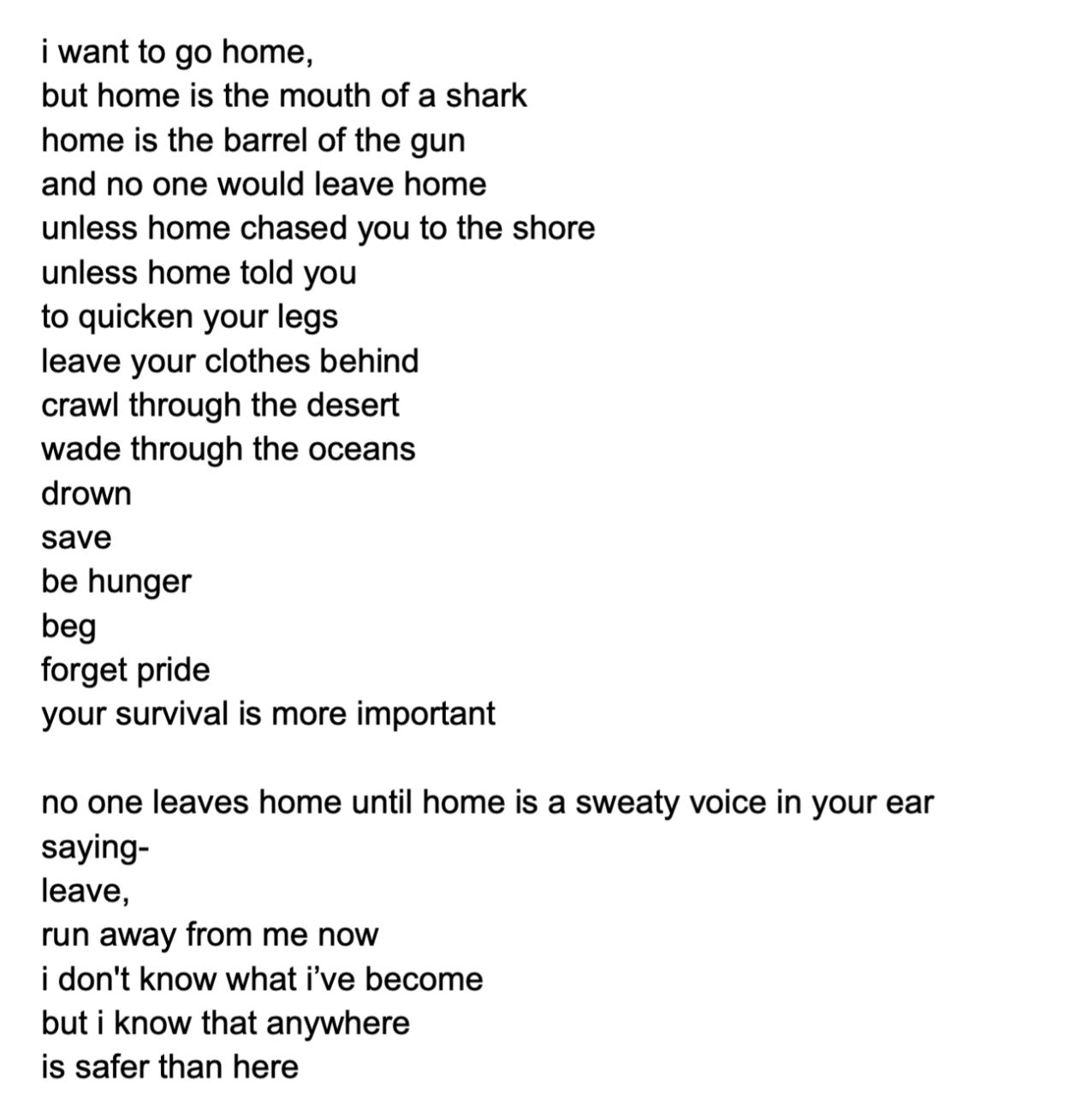

The United States, in its short 250-year history, hasn’t always stood for turning away those who arrive at its borders. A poem many Americans know at least a part of by heart speaks to the tradition of welcoming strangers and shielding those fleeing sharks’ mouths: “Give me your tired, your poor / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free” (from “The New Colossus,” Emma Lazarus, etched into Lady Liberty’s pedestal).

In 1948, the United States and 48 other countries voted in favor of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). And on December 10, 1948, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the declaration. The UDHR recognizes “the inherent dignity” and “the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family” as “the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.” In thirty articles, it establishes rights for all human beings, including that “everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.” In 1952, the US Immigration and Nationality Act provided for this right by way of humanitarian parole.9

As for the US-Mexico border, up until the late 1970s, the border was open. People crossed regularly. People from Mexico crossed to work on farms when farmers needed help and returned carrying US purchases, supporting local US economy. Leading a multinational life was an accepted norm.

And alongside every government policy aimed at spurning migrants, US citizens have gathered and organized to provide aid and succor. The organizations Lisa has worked with are a mere handful of many that have sprung to life in open, defiant response to what they see as the US government’s failure to honor the right of asylum and tradition of welcome. During the mass deportations of the 1980s, a “twentieth-century underground railroad” spread across the desert outside Lisa’s window. At the height of this aid, 580 houses of worship of all faiths provided food and shelter to refugees in search of safety. One among them, Casa Romero, went from aiding 150 migrants a year to 150 daily.10 The organizations mentioned in this series are part of a network that has arisen to meet this need in more recent times.11

Camila prayed. She begged God to provide any other answer than the one that would tear her in two. At last, she knew what she had to do. She took Carlos to the bridge at the port that connected Mexico with the United States. And she watched him cross to the other side alone, pleading that her broken heart would be her son’s salvation.

It was yet another policy shift that sent Lisa to yet another organization, this time into the desert to distribute supplies (see, “No están solas,” in part II): The Biden administration ended MPP on January 20, 2021. Its replacement with CBP One, an app that allowed 1,450 asylum seekers a day to schedule appointments, enabled safety seekers to once again await hearings stateside. But it prevented humanitarian volunteers from applying for parole on their behalf.

This was when Camila crossed into the United States. Soon, she reunited with Carlos. Lisa’s text comes through, and I take in the graduation photo. Carlos, no longer a boy but still with a boy’s round cheeks, wears a mustache and a large silver belt buckle. His gown hangs loosely on his shoulders. His cap rests atop Camila’s head. It matches her royal blue dress held by a silver clasp. She holds him close, her expression one all parents know well, a mix of pride, adoration, and relief.

A window onto migration, aid, and policy now and in the next four years

Lisa explains that Camila has texted to say her case was dismissed; she paid an attorney $5,000 to help her accomplish this.

The hesitation in Lisa’s voice becomes clear as she adds, swallowing hard, “I don’t think they’re in a very safe place now.”

She means safe from the crackdown that’s already seen people deported, not in commercial planes, standard practice, but, rather, manacled in the cold, hard belly of military cargo planes. She means safe from the propaganda campaign doing its best to paint the mom and new high school graduate as “criminal aliens” and “invaders.” She means safe from the hatred and even brutish treatment many migrants receive from US neighbors who believe what they’re being told. She means, after all they’ve been through, safe from the possibility of being sent back to Honduras—or worse.

I will, as I’m finalizing this piece, be pretty sure she saw the escalation that would come in the next few months far more clearly than I did—that she understood just how rapidly worse would come.

Are volunteers worried? “Are you kidding me?” Lisa says, fiery. “We’re all worried like crazy.”

Lisa fears for Elena, too. Though still facing multiple stress- and trauma-related health issues, Elena has been reunited with her husband and eldest son. The family of five, the two littles no longer toddlers, have found a home with a fenced yard and a cat and a dog in rural US South.

“But they live in terror,” Lisa says, “basically hiding in their home.”

Only they can’t just hide. Elena and her husband have to work. The kids have to go to school.

A couple months back, alerted to a pending ICE raid on the restaurant where both parents are employed, the parents stayed home for a day. The owner withheld three days’ pay from each of them. But there was nothing they could do about the injustice. They have no recourse, no matter how criminal the treatment they receive—not even when it’s as egregious as the next story she shares.

One day, Elena called Lisa, hysterical. Her eldest, then 12, had been in the yard with the dog when a neighbor walked up, pulled a gun, and shot the dog between the eyes. Lisa helped them find a veterinarian tech, who was able to save the dog’s life. Two other dogs who belonged to immigrant families, also shot that night in the same small town, weren’t so lucky. No one pressed charges. Her family still sees the shooter regularly.

Elena’s in a limbo only slightly different than Camila’s. She, too, found a lawyer (who took her case on pro bono). Only her request for dismissal was denied.

I hear Lisa shuffle and what sounds like elbows hitting a desk. I know she has a headache. But before I can offer again to continue later, she presses on. I imagine her holding her hair back, hands at her temples, as she explains. It’s a no-win situation. First, there’s the matter of asylum. The criteria is so high or, rather, so specific, almost no one gets it. A person must prove (1) prosecution (2) motivated by (3) a protected ground (race/ethnicity, nationality, religion, political opinion, or particular social group) (4) perpetrated by a government actor or a government unwilling to provide protection and (5) the inability to relocate within one’s home country. Just 1 percent who applied during MPP (of 42,012 cases, only 521) were granted asylum.12

So Elena has a year and a half to build a life with her family, to celebrate milestones like her son’s recent sixth birthday, to long to feel safe to chaperone her daughter’s field trips (when she explained why she couldn’t attend one recently, her daughter pleaded, and mother and daughter cried together). Then she’ll have her asylum hearing.

“And she won’t get it,” Lisa says. For the first time in these conversations, her tone becomes truly deflated. “You could have your entire family gunned down in your driveway and not prove just a single element and be sent back.” She lets out a deep breath into the silence.

The situation isn’t much better for Camila and Carlos and Elena’s husband and older son. They may no longer be under deportation order or facing hearings they can’t win. But they also have no legal standing in the United States. Each is just a “tail light out” away from deportation—or worse.

Even before the recent ramp-ups of raids and threats, crossing the border “illegally” once has been a civil offense that can lead to deportation. Once deported, a person has to wait either three or ten years to reapply. For most, that’s three to ten years of anniversaries and homework sessions, of rites of passage and setbacks without seeing close loved ones. And second unauthorized crossing could lead to incarceration, deportation, and no future possibility of entering legally.

Now the second Trump administration is changing even what it means to enter / to have entered legally. Its day one orders shuttered the US refugee program, stranding 60,000 people who’d already been approved for resettlement. Among them were 1,600 Afghans fleeing because of ties to US forces. Another order revoked the legal status of 530,000 humanitarian parolees who’d fled Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. The Laken Riley Act, the second Trump administration’s first bill, mandates the incarceration of undocumented immigrants at the point of arrest on suspicion, not conviction, of low-level crimes like shoplifting. And just last week, green card holders, lawful permanent residents, were told that, if they’re found to be in violation of immigration laws, they could lose their legal status and face deportation.

“They live in terror, basically hiding in their home.”

Lisa wishes people knew the truth. She wishes that, when they heard the label “criminal alien,” they would see, instead of whatever image is conjured, Elena and Camila and Carlos, people trying to reunite with and protect their families. When Lisa first arrived in the borderlands, she wrote and wrote and shared photos on social media. “I just wanted people to see what I was seeing and care enough to do something,” she says. “We have to counter the false narratives.”

Those who provide aid to immigrants and migrants are also in the administration’s sights. Day one orders canceled the ban on immigration agents entering sensitive places—churches, schools, and hospitals. As of late February, lawmakers in 20 states filed legislation targeting sanctuary policies limiting cooperation with immigration authorities, threatening lawsuits, fines, and jail time.

Are volunteers worried? “Are you kidding me?” Lisa says, fiery. “We’re all worried like crazy.”

But it won’t stop humanitarian volunteers like her from aiding those who migrate here in search of safety and freedom. Lisa and others will keep welcoming new neighbors and friends. They’ll keep connecting the Juans with medical aid (the thirteen-year-old from part I who lost his leg to “La Bestia), the Diegos with water and food (the diabetic wandering alone in the desert for days), and the Camilas and Elenas with their loved ones. “I mean, come on. People are dying,” she says, and I picture her silvered black curls flying. “And people shouldn’t be dying because they don’t have water.”

Lisa pauses, and I can sense her eyes narrowing as if surveying a classroom, can feel her getting ready to project to the back of the room for those not paying attention. “Migration is never going to end. People have migrated since the beginning of time. Our ancestors migrated—way back before we evolved into Homo sapiens.” A wry chuckle weaves its way into her tone as she adds, “And the sapiens part’s a joke.”

A profusion of human movement

Lisa’s right. And humanity is currently amid a profusion of movement. Some 281 million people—3.6 percent of the global population—live in a country where they weren’t born. Nearly 114 million, mostly from the global south and a third of them children, have been forcibly displaced and made stateless due to violence, persecution, poverty, and climate-related disasters. That’s 1 in 67 people worldwide forcibly displaced, per the UN Refugee Agency.13 People running for their lives will keep running. People drawn to move to new homes for love or work or desire for newness will keep moving to new homes.

Meanwhile, the United States, like many countries from the global north, needs more people. The US birthrate has been below replacement level since 1971, per Centers for Disease Control statistics.14 Immigration has kept the US economy and population from stagnation. In 2023, households led by undocumented immigrants paid $89.8 billion in taxes. Diversity enriches our lives—bringing new foods, new ideas, new solutions, new neighbors, new members of the human family to interact with and learn from.

And that commingled, multinational community Lisa sees in her desert isn’t rare. Rather, it’s a version of what we all in the United States see out our windows, whether we realize it or not. As of 2022, 34.7 million people born in other countries were making their homes in the United States legally; 11 million more are estimated to be living here undocumented. Another 36 million of us have at least one parent who was born in another country. And third-generation and higher-tier generations comprise 235 million people (that’s 75 percent of the US population whose family hails from elsewhere just a few generations back).

As we talk, I imagine Lisa looking out onto a quiet twilight. It’s grown late. I imagine the photo of Camila still open in her hand. I comment on my gratitude for all the aid people have provided. “It’s the very least we can do, isn’t it?” she says.

Be sand, or what we can do

I asked Sarah Towle, author of Crossing the Line: Finding America in the Borderlands (2nd edition coming soon), an important resource for me and many others, what we can do about what’s being done in our names. “We have no choice but to be a billion tiny grains of sand thrown into the machinery to keep the gears from turning,” she wrote back.

Education is key, says Towle. She wrote Crossing the Line because she knew people would be outraged if they knew what was going on. We can learn what’s going on. We can grow the number of people by talking to neighbors and loved ones. We can share the information we find.

A next step is to create possibilities or encounters. Any way to put potential allies in touch with “the folks being vilified by the bad guys”—so they’ll see for themselves these people “are not criminals at all—is huge. She told me about organizing a party so her friends could meet some people who’d just arrived from Cameroon. When one of her Cameroonian story collaborators was called in for an unexpected ICE check-in and needed accompaniment, her friends went with him. “And now they are committed immigration activists willing to put their bodies between ICE and the most vulnerable among us,” she wrote. “So, no matter which comes first—seeing an ICE raid, and then wanting information; or getting educated, then encountering—these are the baselines for moving most folks from outrage to action.

Call to Action

In her most recent post, “Our Basic Rights Are Under Attack,” ’s Call to Action gives specific steps we can take to help inform ourselves and share with our friends and neighbors the truth about migration, US immigration policy, what’s being done in our names right now, and why that’s a threat to us all and to help those living in fear access food and safety.

Thank you for reading and liking and commenting. Please share or, if you’re on Substack, restack “Sharks Mouth III: Torn Apart, Brought Back Together.”

I would love to spread the stories of Lisa, of Elena and Camila and their families, and of Lucia, Juan, and Diego far and wide.

Coming soon, look for a Substack live between and me. We’ll focus on more ways to be billions of tiny grains of sand thrown into the machinery.

Thank you to new (and all) paid subscribers and patrons (founders). Your support helps keep this desk, now in the heart of a somewhat troubled beast called Vivian, rolling. In coming months, I hope to roll toward the US/Mexico border and elsewhere to learn and share more of these stories up close and personal.

All of this is a labor of love. But it’s not free. Your support helps keep gas in the tanks, mine and Vivian’s.

And for however you subscribe, thank you for being here. I am truly deeply grateful for you all.

Join in. Read weekly. Become a paid subscriber or patron (founding subscriber). Keep this desk rolling to where the stories are.

Leila Fadel, “Masked immigration agents are spurring fear and confusion across the U.S.,” NPR, July 10, 2025; Claire Moses, “L.A. Area Bishop Excuses Faithful From Mass Over Fear of Immigration Raids,” The New York Times, July 10, 2025; Billal Rahman, “Immigration Officials Issue New Warning to Green Card Holders,” Newsweek, July 9, 2025.

The University of Arizona, “A Brief Legislative History of the Last 50 Years on the U.S.-Mexico Border,” Mexico Initiatives, April 28, 2020; Human Rights Watch, “Statement of Human Rights Watch: The Human Cost of Harsh US Immigration Deterrence Policies,” Before the US House Homeland Security Committee, July 26, 2023; Undocumented Migration Project (UMP), “Hostile Terrain 94 (HT94),” a participatory art project composed of over 4,000 handwritten toe tags that represent migrants who have died trying to cross the Sonoran Desert of Arizona between the mid-1990s and 2024; Walter A Ewing, “‘Enemy Territory’: Immigration Enforcement in the US-Mexico Borderlands,” Center for Migration Studies, 2014; Eric Reidy, “How the US-Mexico border became an unrelenting humanitarian crisis,” The New Humanitarian, May 10, 2023.

American Immigration Council, “The ‘Migrant Protection Protocols’: an Explanation of the Remain in Mexico Program, Fact Sheet,” February 1, 2024.

Sarah Towle, Crossing the Line: Finding America in the Borderlands, She Writes Press, 2024.

University of Arizona, “Brief Legislative History”; Towle, “Crossing the Line.”

Tom Kisken, Ernesto Centeno, AraujoIsaiah Murtaugh, Cheri Carlson, and Dominic Massimino, “Federal immigration agents blockade Camarillo farm, clash with demonstrators,” VC Star, July 10, 2025; Mandi Teheri and Gabe Whisnant, “Farm Worker Dies in California ICE Raid, US Citizens Missing, Union Says,” Newsweek, July 11, 2025.

Juliana Kim, “How Trump's tax cut and policy bill aims to 'supercharge' immigration enforcement,” NPR, July 3, 2025.

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), “Court Approves Historic Settlement in ACLU’s Family Separation Lawsuit,” press release, December 8, 2023.

United Nations, “Universal Declaration of Human Rights”; Office of the Historian, “The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (The McCarran-Walter Act),” US Department of State.

Towle, “Crossing the Line.”

A list of the organizations mentioned in the “Sharks’ Mouths” series: Shelters for Hope, Ajo Samaritans, Al Otro Lado (The Other Side), Each Step Home, Humane Borders / Fronteras Compasivas, No Mas Muertes / No More Deaths.

American Immigration Council, “The ‘Migrant Protection Protocols.’”

Brady E. Hamilton, Joyce A. Martin, and Michelle J.K. Osterman, “Vital Statistics Rapid Release,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, April 2024; UNHCR, The UN Refugee Agency, “Mid-Year Trends,” October 9, 2024.

Hamilton, et al, “Vital Statistics.”

The "like" icon feels somehow inappropriate, and the "restack" pretentious. Yet from across the globe, all I can do is tell you: I have read this, this hurts, this matters.

Wow, Holly! What beautiful storytelling. Your powers of observation are profound and so poetically evoked. Your reporting is critical and well-sourced, and your message is spot on! Thank you not simply for joining the choir of resistance singing in ever-louder harmony, THE CRUELTY IS NOT OKAY! THIS IS NOT THE PEOPLE WE WISH TO BE!, but for becoming one of its soloists through this very important and moving series. As I read, I felt like I knew Lisa and Elena, Camila and Diego from my own reporting across the 2000-mile US/Mexico line for Crossing the Line. Thank you for becoming a handful of sand and for bringing others into the fold with your storytelling. I will share it far and wide. Meantime, I look forward to our coming conversation. As for my Call To Action to align with your series, here's the link: https://open.substack.com/pub/sarahtowle/p/our-basic-rights-are-under-attack?r=464pd&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true.

Stay strong, my friend. The only way through these dark times ahead is . . . together.

In solidarity and storytelling, Sarah