Sharks' Mouths I: Fear and Confusion, Tamales and Kings

A Political Landscape Long Feared by Immigration Advocates

Hi! I’m glad you’re here.

I’ve been thinking of my why. Why do I write? Nomad? Engage? To connect, of course, is huge. And holy damn has it worked here—i.e. you!

For the next few weeks, I want to share with you a reported story I’ve been working on for a while, developed in conversation with a humanitarian aid volunteer at the US/Mexico border. Her name and identifying details, along with those whose stories she’s connected me to, have been changed for their protection.

I write this to open my eyes. To probe a history that’s played out, for many of us, largely in the shadows of simplistic narratives and false dichotomies—of US immigration policy, of aid, of the meeting of our fellow human beings who seek sanctuary with us. I write this to interrogate what human migration means for all of us and the changing perspective on that understanding in the United States and beyond. I write this to be clear-eyed about what has been done and what is now being done “on my behalf.”

I share it as a bridge.

I. Fear and confusion, tamales and kings

When “Lisa,” a humanitarian aid volunteer, looks out her window in Ajo, Arizona, not far from the Ajo / Sonoyta, Sonora, border these days, she wants to scream. She sees, among stark beauty and a blend of cultures, the aftermath of a volley of Trump administration Day One immigration orders—a political and cultural landscape activists have long feared, devoid of sympathy for all immigrants, regardless of status.

She sees a stifling fear and confusion among aids and migrants alike.

(My conversations with Lisa took place at the beginning of the year, just after that flurry of executive orders, and through early spring. To take in the media I consume is to understand that fear and confusion rocking Lisa’s world have no doubt skyrocketed since: News reports show migrants imprisoned in confinement centers like Guantanamo and Cecot. Posts from government accounts threaten the stripping of former legal status, including the dismantling of the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of birthright citizenship. Videos depict often unidentified, masked men effecting the disappearances of students and people pulled over for routine traffic stops. Department of Homeland Security secretary, Kristi Noem, and White House deputy chief of staff, Stephen Miller pressed immigration officials to make 3,000 immigration-related arrests per day.1)

Lisa’s immediate response to what the border is like that first month is quick and heated: “Nobody knows what the fuck is going on,” she snaps. We’ve met a handful of times in the past, so even over the phone, in the silence that follows, I can picture her shaking loose silver-and-amber curls, dark eyes flaring.

To me, Lisa comes across as one of those people who are buoyed by an inherent hopefulness. So in moments like this, I can find myself taken aback by the despair I hear in her tone. But as we continue to talk, the passion that is the other side of that coin is impossible to miss. And I’ll come to understand, months on, what else she was seeing: Flying past a vast desert known for death and abundance (she was in a car during this first conversation)—a desert she’s walked, leaving water, food, and blankets along known migrant routes—she had a far better idea of what was coming than most.

The ramping up of a failed tactic

Retirement, coupled with a desire to welcome those who come to the United States seeking shelter, brought Lisa to this desert more than a decade ago. Guided by evolving DC policy, she’s volunteered with a revolving door of aid organizations. So she’s witnessed, up close and personal, the human forms each change takes—a child crossing a bridge alone, a mother holding her breath on the other side; a 13-year old with a missing leg; a mother assaulted, her toddlers captive; a man, lost and wandering under unrelenting sun, to name a few. You’ll meet these people.

Lisa has seen misery deployed to stop migration. She’s seen parents shackled, their children taken in another direction. She’s seen people bolting, wild with fright, when a helicopter dives. She’s seen remains, still mostly a body.

For her and other aids, a refrain by poet Warsan Shire explains why the tactic fails miserably again and again: “No one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark.”

Now, Lisa sees the United States being fashioned into an even more brutal mouth filled with jagged teeth than it has already been.

Those Day One orders—packaged as, “Protecting American People Against Foreign Invasion”—recast migration as invasion. The declaration of a national emergency at the border and the reclassification of cartels and gangs as terrorist organizations paved the way for military intervention and the treatment of sanctuary givers as enemies.

Lisa sees the truth about the invasion. “When people call us and ask us for supplies, do you know what they need?” she says, haughty, clear, spelling it out for those in the back of the room. “They need diapers. They need baby formula. They need baby bottles. That’s who’s invading the country. It’s families with kids.”

“When people call us and ask us for supplies, do you know what they need? They need diapers. They need baby formula. They need baby bottles. That’s who’s invading the country. It’s families with kids.”

By May, just a couple months after this conversation, more than 200 men and boys had been shipped to El Salvador and imprisoned at Cecot, a terrorism confinement center notorious for human rights abuses. Among those sent were a teenager on the way to volleyball practice, a young father picking up baby formula, and construction workers on their way to jobs—all taken during routine traffic stops. Sent too, a makeup artist whose crown tattoos on his arms, referencing Three Kings Day, a celebration of the three wisemen’s gifts at the end of the Twelve Days of Christmas, seems to have been the reason for his arrest. Of the 90 men flown to CECOT whose US entries a libertarian think tank called Cato analyzed, more than half came to the United States legally.2

Early into its term, the Trump administration promised to imprison 30,000 migrants at the Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, naval base known as “Gitmo,” also infamous for inhumane conditions. A congressional delegation reports that, as of June, about 500 migrants have been sent to the camp. But, per documents obtained by POLITICO, the government plans to ramp those numbers up quickly. Though the administration isn’t giving much by way of specifics on who the Gitmo detainees are, civil rights lawyers have filed suits to stop the transports. And according to one lawsuit, two of the men had been tortured by the Venezuelan government for their political views, one from Afghanistan and one from Pakistan came to the US due to Taliban threats, and another fled Bangladesh after being threatened over his political party membership.3

As for US-based Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention centers, reports of overcrowding, starvation due to severe lack of food or spoiled food, medical neglect, conditions like only floorspace to sleep on, and abuse are widespread.4

Still, the White House, through Miller, threatened to fire senior ICE officials if they don’t start detaining 3,000 migrants a day, an aim for which the Trump administrations has asked for an additional $45 billion (over the $3.4 billion budget already in place). Tom Homan, border czar, promised, in an interview with the New York Times, to “flood the zone,” and confirmed that, sometimes, migrants are deported to third countries to which they have no connection. When pressed, he said that, while ICE is going after “criminals,” to come into the country illegally is itself a crime, and anyone caught undocumented will be detained.5

ICE statistics show the number of people with no other criminal charges or convictions swelled—from about 860 in January to 7,800 this month—an 800 percent increase, as compared to a 91 percent increase in those with other charges or convictions detained.6 As to the 3,000 daily arrests, simple math tells you that would mean 90,000 per month and, over a single year, more than 1 million people detained, confined, and/or deported.

“Cruelty is the point. They’re going to cause suffering at every step in every way they can.”

Lisa tells me about a Venezuelan mother living in Tucson, Arizona, who a colleague of hers was trying to find. The mother had disappeared after being pulled over for driving too slowly in early February. Local news reported her missing, along with two of her children, following the traffic stop, no records to be found. Meanwhile, Lisa’s colleague met with the woman’s frantic husband.

Eventually, what had happened to the mother and children unfolded. ICE agents, called to the stop, had taken the mother and the two of her four children who were with her to the US/Mexico border, ignoring her pleas to at least let her call and make arrangements for her other kids—at home and expecting her to return shortly. The agents had told her that wasn’t their problem. Then, as her 9-year-old son pleaded with them to stop talking to his mom like they were, they’d handcuffed her and escorted the trio onto a bus. Two days later, mother and children had been abandoned in southern Mexico, where they knew no one, with nothing but the clothes they were wearing.

“Cruelty is the point.” Lisa sighs, her tone flattening. “They’re going to cause suffering at every step in every way they can.”

Three + nations weaving community

Early last year, the window above Lisa’s stove was fogged over. The aroma of meat stewing, filling for more than 200 tamales, saturated every corner of the house. At a recent Three Kings Day celebration, she’d received the piece of La Rosca de Reyes (the bread of kings) with a plastic baby Jesus baked in—earning her the honor of food prep for a follow-up gathering. Two Mexican friends who live in Ajo came to her place. They showed her how to mix the masa and spread it onto husks, the trio working in unison. “My kitchen was wrecked.” She cackles. The expression now on her face, a mix of pleasure and mischief, is another I can imagine without seeing her, as I’ve seen it before.

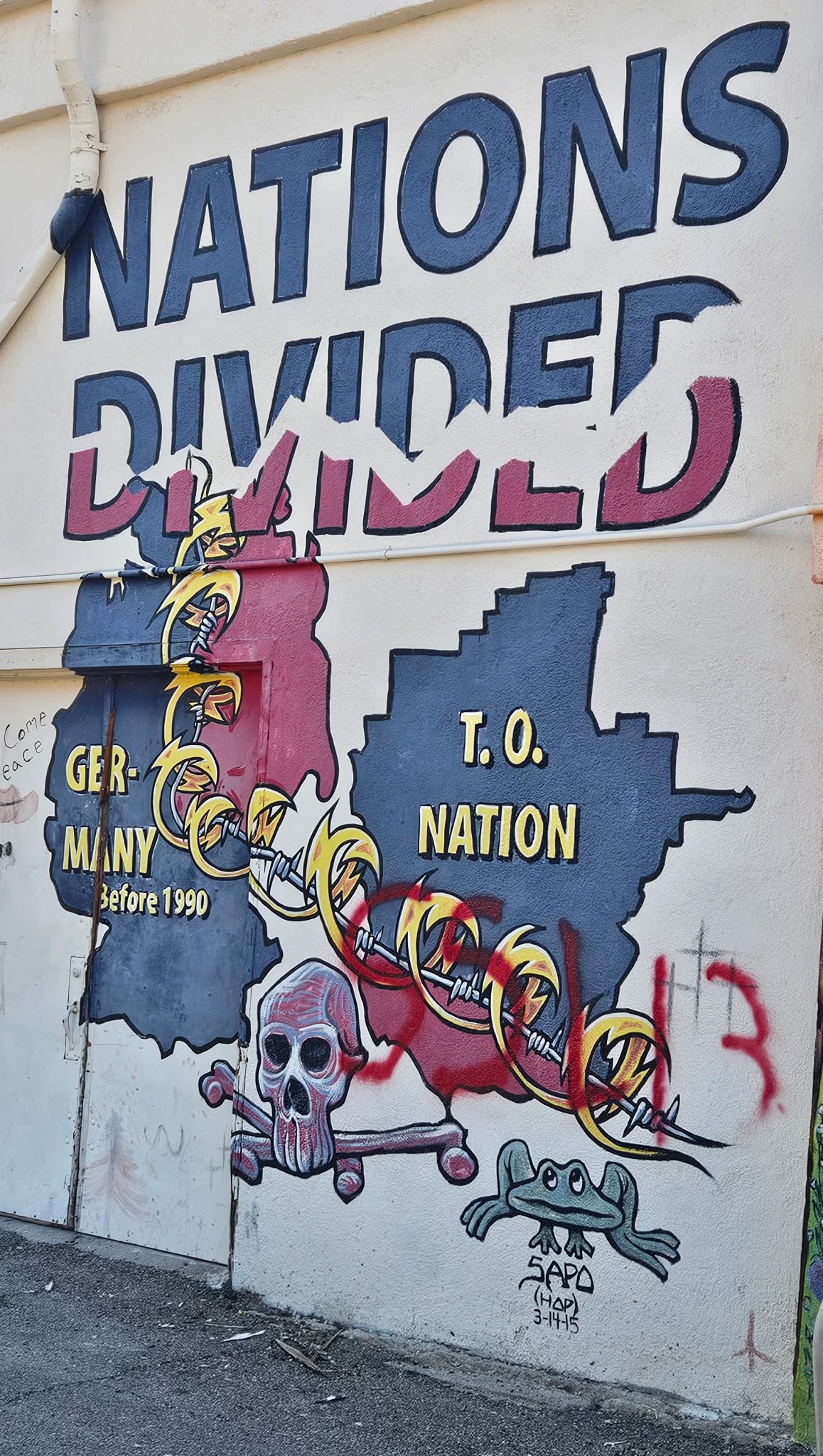

It’s easy to picture her there in that kitchen, too, apron over ubiquitous loose jeans, worn at the knees from endless hours of working soil and harvesting produce she processes and shares, long wavy locks wild or tied at the nape of her neck. Though I’m not actually certain of the exact view, I imagine that, through the steamed glass, she might be able to see Ajo’s historic plaza. I envision the flags of three nations—Mexico, the United States, and the Tohono O’odham, a sovereign nation whose territory stretches between the two—fluttering over the square where the community has celebrated International Peace Day each September for the past two decades.

A commingling of cultures has defined the area since long before 1924, when the United States first established its southern border. It was the late 1800s when the land of the Tohono O’odham was split by the two governments. Now many employees of local businesses cross the border daily. And like Lisa’s dinner table, families, both those who live in the region permanently and those who travel to the border in hopes of crossing, are often tri-national—at least.

As we talk this time, Lisa has just returned from a second annual gathering, this one in Mexico. Dia de la Amistad (Day of Friendship) is held in February in Sonoyta to include those unable to make the US crossing for the September gathering. She’s elated, if exhausted, still riding the high of connection and celebration. This year, Shelters for Hope, one of the places she volunteers, was invited to participate in the parade for the first time. So children from the shelter marched alongside kids from local schools, all waving their home countries’ flags, which they’d made by hand. Among the shelter youth, seven flags flew.

“It was a moment of such pride,” Lisa says, her voice rough with the astonishment of becoming swept up, once again, in joy among people who’ve lost nearly everything and still believe “God is good.” It’s a refrain she hears often.

She sends me photos, reminding me I can’t share any that show faces. Two vie for my favorite. In one a girl, maybe 4, beads around her neck and neon bows on her shoes, wears an expression of pure concentration; whatever has her attention is off camera, but still I catch myself almost turning to look.

The other shows a slightly older boy looking up, maybe at a stage, his eyes wide with wonder. Even turned from the camera, the young woman he’s with (maybe his mother?) exudes exhilaration. My breath catches as I imagine the relief she must feel to be celebrating after what was surely a perilous trek to this moment.

As for the little one in the stroller, chubby-cheeked and button-nosed, I want to scoop him up. Maybe I could learn from him; gaze toward the camera, he’s caught amid that far-off, intense stare toddlers sometimes get, like they’re seeing something the rest of us miss.

During a break from face painting and jewelry making, Lisa helped “Lucia,” the mother of the button-nosed toddler, push him in a broken-wheeled stroller. For eight months, the mother of two had a daily ritual: Open the CBP One app, hope singing in her chest. Each day, two words stared back: “Case pending.” During her time at the shelter, Lucia knew of only four families who received an asylum hearing date.

On January 20, 2025, any appointments scheduled were summarily canceled. The only road to seek asylum was closed. And so everyone at the shelter (160 people in February) is stranded indefinitely. And this is one, a smaller one of many, many shelters and encampments along the nearly 2,000-mile border.

“It was a moment of such pride,” Lisa says, her voice rough with the astonishment of becoming swept up, once again, in joy among people who’ve lost nearly everything and still believe “God is good.” It’s a refrain she hears often.

Watching the parade, Lisa thought of 13-year-old “Juan,” in desperate need of medical attention and also stuck in limbo. Like many traveling north through Mexico, Juan and his mother mounted the roof of a massive train known as “La Bestia” (the Beast). At some point, Juan lost his balance. His mother watched in horror as he toppled. Far below on the tracks, his leg was crushed beneath the wheels of the Beast.

Keenly aware the crude above-the-knee amputation needs care to heal, Lisa pressed to get Juan into the United States before January 20, only to be met by the wall of an app not equipped to expedite the process. Now, she’s working with the owner of a new prosthetics company and still searching for a medical team. She’s learned that Juan’s leg will, by no means, be the first limb the company has provided for a migrant who’s survived an encounter with La Bestia.

Lisa is glad Juan and his mother came to this particular shelter for help. Unlike many shelters at other entry ports, the one in Sonoyta is relatively safe, and the families live well together.

As Lisa recalls the day of the tamales, only weeks before January 20, I can see it in my mind: There’s bright-eyed grin she’s known for. There are the events of the day playing out like a long, comforting sigh—including both crossings between countries. In a way, it will come to seem to me a crossing between times too (especially given what she relates the next time we talk, shortly after another crossing).

On the way into Mexico that morning, Lisa’s car brimmed with tamales and anticipation. At the shelter, the women boiled them in huge pots over wood fires. All who’d gathered ate like royalty, shared stories, and played games. Heading back to the United States, under starlight, it was Lisa’s belly and heart that were full.

Thank you for reading and liking and commenting. Please share or, if you’re on Substack, restack “Sharks Mouth I: Fear and Confusion.” I would love to spread the stories of Lisa, Lucia, Juan, and the others far and wide. Over the next two weeks, I’ll share more of Lisa’s view, more migrant stories, and more of the braided history of policy and aid, of turning away and welcome at the US borders and beyond.

Thank you to new (and all) paid subscribers and founding members! Your support helps keep this desk, now in the heart of a beast called Vivian, rolling. In coming months, I hope to roll toward the US/Mexico border and elsewhere to learn and share more of these stories up close and personal. All of this is a labor of love. But it’s not free. Your support helps keep gas in the tanks, mine and Vivian’s.

And for however you subscribe, thank you for being here. I am truly deeply grateful for you all.

For the comments, have you ever lived or thought of living somewhere you weren’t born? Do you know anyone who’s had to leave a place (a home, a city, a state, a neighborhood) in order to find safety? Are you, like me, hungry for tamales right about now?

To help keep this desk rolling to where the stories are.

Coral Murphy Marcos, “At least 50 migrants sent to El Salvador prison entered US legally, report finds,” The Guardian, May 19, 2025; Sacha Pfeiffer, “Trump said he'd send 30,000 migrants to Guantánamo. He's sent about 500,” NPR, June 23, 2025; Nahal Toosi and Myah Ward, “Trump team plans to send thousands of migrants to Guantanamo starting as soon as this week,” Politico, June 6, 2025; Ray Sanchez and Alisha Ebrahimji, “Masked ICE officers: The new calling card of the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown,” CNN, June 21, 2025.

“How Trump is turning a routine traffic stop into a weapon for deportation,” The Economic Times, June 23, 2025 (traffic stops); Marcos, “At Least 50” (makeup artist, stripped of status).

Pfeiffer, “Trump said he’d send 30,000,” (500 per delegation); "Toes and Ward, “Trump team plans to send thousands” (ramp-up goal); “Lawyers sue to stop Trump administration from sending 10 migrants to Guantanamo Bay,” PBS News, March 1, 2025 (lawsuit).

Jasmine Garsd, “In recorded calls, reports of overcrowding and lack of food at ICE detention centers,” NPR, June 6, 2025 (detention center conditions) and Nazish Dholakia, The Truth About Immigration Detention in the United States, June 11, 2025.

Julia Ainsley, Ryan J. Reilly, Allan Smith, Ken Dilanian and Sarah Fitzpatrick, “A sweeping new ICE operation shows how Trump's focus on immigration is reshaping federal law enforcement,” NBC News, June 4, 2025 (3,000 a day); José Olivares, “US immigration officers ordered to arrest more people even without warrants, The Guardian, June 4, 2025.; Allison McCann, Alexandra Berzon, and Hamed Aleaziz, “Trump Administration Aims to Spend $45 Billion to Expand Immigrant Detention,” The New York Times, April 7, 2025 ($45 billion); Natalie Kitroeff, “An Interview with Trump’s Border Czar, Tom Homan,” New York Times, The Daily, June 19, 2025 (border czar).

Ted Hesson, “Trump's immigration enforcement record so far, by the numbers,” Reuters, June 17, 2025.

Intentional cruelty. I watched the video of a man in L.A. yelling at ICE agents. He was saying things like, "Are you proud of what you're doing?" My heart aches with the need to help people understand that migrants are not the reason they've lost jobs, that healthcare is unaffordable, that groceries are too expensive, that our streets are, admittedly, unsafe in many places. I understand that everyone is hurting. I don't understand how easily we are duped into accepting the propaganda we are fed by those in charge.

Who but someone who had no other choice would risk such a crossing?

Thank you, Holly, for the months of work that went into this piece, for the wholeheartedness of it, for the eloquence of it, for connecting us to Lisa and to her causes, to the fellow human beings she gives herself to time and again.

Sadness overcomes me each time I hear these stories. What has happened to the spirit America was built upon?! Inconceivable times we are living through... J