Hi. Thank you for being here.

This is the second installment of a three-part reported story, “Sharks’ Mouths: A Political Landscape Long Feared by Immigration Advocates,” developed in conversation with a humanitarian aid volunteer at the US/Mexico border. Her name and identifying details, along with those whose stories she’s connected me to, have been changed for their protection.

Read part I—“Fear and Confusion, Tamales and Kings.” Since its posting last week, the fear and confusion for those who would migrate or have migrated to the United States and those who would welcome them have no doubt skyrocketed once more. With the signing of the Trump administration’s massive domestic policy bill two days ago on July 4, an additional $157 billion have been allocated to support the administration’s border and immigration goals.1 Today, stories from the border. Next week, we’ll meet people who’ve migrated and are currently within the US borders.

II. Two Truths and So Many Lies

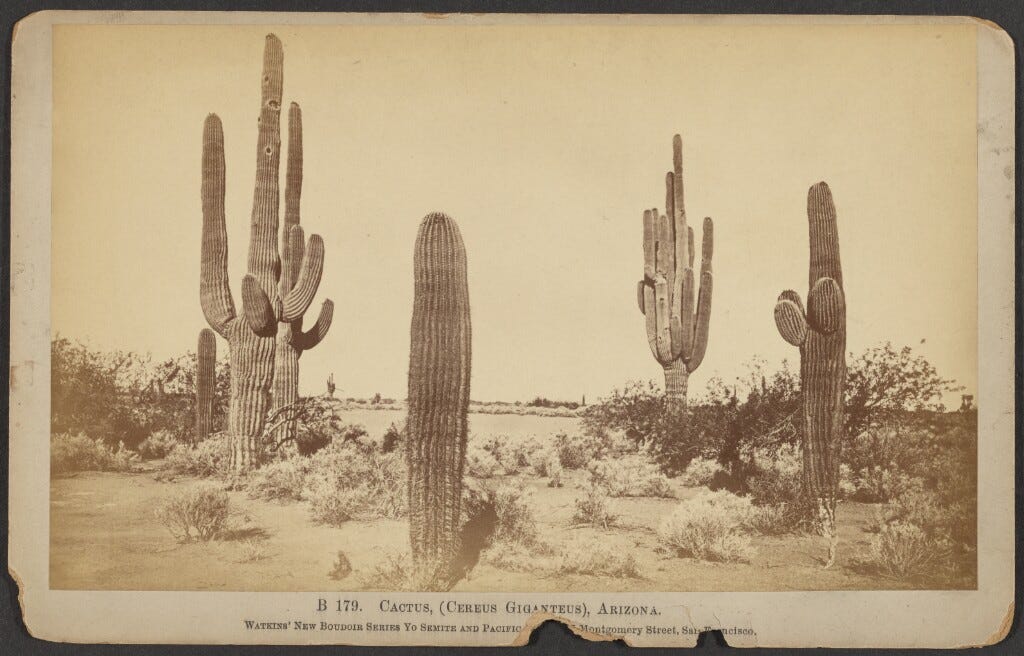

I ask “Lisa” (a humanitarian aid volunteer at the US/Mexico border) to take us on a trip to and beyond the US port of entry closest to her Ajo, Arizona, home. She explains that, to get to the crossing from Ajo, we first pass through Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. A 299-acre slice of the Sonoran Desert, Organ Pipe has, per the National Park Service website, “something for everyone to enjoy.” Think stunning wildflowers, scenic biking and hiking, and dazzling stargazing. And then there are the echoes “of human stories chronicling thousands of years of desert living.”2

Next, says Lisa, who I’m learning doesn’t hide how she feels (a quality I appreciate), we climb a hill that’s “an ecological nightmare.” I can almost feel the disgust coming across the phone line as she adds, “And then there’s this total clusterfuck of a wall.”

Now we’ve arrived at the US Customs and Border Patrol (CBP), Lukeville Port of Entry, established in 1949. It looks like any other small, mostly quiet border crossing—two paved lanes divided by orange barriers, guards in a booth, signs directing traffic based on whether you do or don’t have anything to declare. Alone on the north side is a now defunct hotel called Gringo Pass.

Drive or walk through. And, boom, you’re in the city of Sonoyta, Sonora, Mexico. Everything comes alive. Loose dogs run amok. Window cleaners approach if you’re in a vehicle. Blocks of concrete and rebar mark construction projects in perpetual limbo.

Just a mile in is Shelters for Hope. The occupants (some 160 people, mostly families) wait. They’ve been waiting. Now their wait is indefinite. On day one of the current Trump administration, an executive order repealed CBP One, an app used by the Biden administration that allowed 1,450 asylum seekers a day to schedule appointments and was credited with a marked drop in unauthorized crossings in 2024—effectively leaving no legal means (no “right way”) for migrants to request asylum within US borders.3

The Lukeville port almost exclusively serves passenger vehicles and pedestrians. A large portion of its traffic consists of tourists headed to and from the popular beach town of Puerto Peñasco, Sonora.

And yet, on December 4, 2023, under the Biden administration, CBP closed the port for what ended up being a month. At the time of the closure, border patrol gave no indication of when the crossing would reopen.4 Lisa recalls the impact on locals on either side—people unable to see their families over the holidays, families with children who bussed across for school faced with a difficult choice (either have the students miss school and fall behind or figure out temporary housing for them in a country they would return from at some indefinite point in the future), and those who crossed daily for employment, too, needing to make a quick choice, between missing work and figuring out where to live in able to keep earning a living.

“It was ridiculous,” Lisa says, noting that the CBP One app (then still functioning) didn’t operate at Lukeville. “It was all for show.” The stated reason for the closure? Moving personnel where they need to be in order to “prioritize border security” and handle a surge of asylum seekers.5 Lisa scoffs. “They moved something like eleven border patrol guards.”

When Lisa returned from Mexico through Lukeville this February, after a gathering called Dia de la Amistad (Day of Friendship), the crossing was nothing like the norm. Recall the nothing-to-report-but-a-full-belly-and-heart crossing after a Three Kings Day tamale fest described in part I—just a month earlier? This crossing was not that. Though her heart was once again full as she headed toward the port, this time, for the first time in countless crossings, she was stopped. Mexican military personnel and dogs searched her and her car for fentanyl. Her text to tell me about it includes the vomiting emoji.

A wall dividing

Lisa sends me photos. Most I can’t use to protect those depicted in them. I take in the wall. Towering steel bollards filled with concrete and rebar slice the desert into twin paths, one called south, the other, north. Only when I see images with people in them—tiny action figures, leaning against the wall in glaring sun, mid-stride alongside it, facial features obscured by its shadow—does the massiveness of this barrier, which ranges from 18 to 30 feet tall, fully strike me. I feel my breath catch in my throat with the sudden understanding of why, in places where this is what the wall is like, its height has been described as a treachery that lives in nightmares, responsible for injury and death.

The wall isn’t contiguous. It simply ends here, is opened there during monsoon seasons, lest it be washed away. It’s comprised of chain link or mesh fencing here, concrete levee there. In places, it’s concertina wire; in others, metal X’s holding railroad ties.

The Trump administration’s multi-tentacled domestic policy bill, signed into law just two days ago on US Independence Day, provides roughly $46.5 billion to complete the wall.6

But the wall, even in the sections made of steel bollard, isn’t particularly hard to breach, not for the cartels anyway. A simple cutting torch will do the trick. Cartels—who’ve controlled unauthorized crossings since US policy made doing so lucrative decades ago—do just that regularly, for a fee. This price of admission is yet another shark’s mouth. Lisa knows about only one man who “crossed” without paying, doing so when he jumped into swirling waters to help a group of women who were flailing, near drowning as they attempted a perilous river crossing. His body was found the next day.

Daily, contractors on the US side go up and down the wall to solder holes, dating and initialing the repairs. Certain spots are smattered with white paint.

I can’t stop looking at a still photo that captures an asylum seeker and her self-portrait taken during a class given by photographer Angel Emilio Chévere. The young woman faces the wall, back to the camera, hair falling to her shoulder blades. She holds the portrait up against the wall, facing herself. The camera catches her piercing gaze. To me, she seems to be at once looking out from behind the bars and beyond them. I imagine I can see in her expression, tight-lipped and resolute, both the memories of all that’s brought her here and her hopes for the future.

And I can’t stop thinking about the Tohono O’odham and how their language has no word for wall. The territory of the sovereign nation stretches between Mexico and the United States. So, on their land, a five-strand barbed wire fence marks the line between the two.7 Lisa sends me a photo of a mural in Ajo’s Artists Alley. In block lettering, the word Nations is solid; Divided, below it, is split in two. The shape of pre-1990 Germany sits next to the shape of “T.O. Nation.” Swirling gold barbed wire cuts through both, a reminder the wire dividing Tohono O’odham land was strung in the same decade the Berlin Wall fell. (See a photo in part 1.)

No están solas

Lisa has joined humanitarian aids picking their way along known migrant routes in the desert for the past two years. They leave water, food, and blankets—the basics necessary to survive an environment where, this time of year, daylight endures for 14 hours, daytime temperatures press triple digits Fahrenheit, and nighttime temps can drop by a startling 50 degrees.

The Sonoran Desert teems with low brush and crucifixion thorn and fuzzy jumping cholla, known for their trippy beauty but painfully barbed if you get too close. It’s home to javelina and sidewinder rattlesnakes, bobcats and coyote; to cardinals and mourning doves and elf owls; to pronghorn and mule deer, horny toads and Gila monsters. Its terrain is diverse. Because only CBP agents are authorized to drive through the desert, the volunteers carry the supplies over treacherous routes on their backs. They hike and sometimes stumble through deep ravines and desert basins, over loose rock, around thick ground cover, up volcanic rock formations, and, from time to time, across human remains. When they find a body, they alert search and rescue teams through a geolocation system; no cell service exists in these desolate areas.

Primary causes of death for migrants in this desert are three. Hyperthermia is the first. Summer temperatures reach triple digits. The second is hypothermia. “You’d be surprised how cold it gets,” Lisa says during a February call, noting she scraped frost off her car the other morning. The third may be more surprising. It’s blisters. “Their feet look like raw hamburger.” I can almost feel Lisa shudder through the phone.

It was way out in the west desert where Lisa met “Diego.” A diabetic, he’d been separated from the group he was traveling with. He’d wandered for four days, with no food, no water, and no medication. The veins in his legs bulged. His front teeth had fallen out. He told them he had to turn himself in, that he was going to die.

To attempt the perilous trek through the desert in order to “enter without inspection,” you must first pay cartels for the privilege. Most who do so are city dwellers. Very few are prepared for the inhospitable environment they find themselves in. “We find abandoned makeup cases and high-heeled shoes,” Lisa says. “These people have no idea what they’re in for.”

Anyone who can’t keep up with the group is left to go it alone.

“And they’re hunted like animals.” This Lisa spits out. I can see her eyes flashing. She references a short story, The Most Dangerous Game by Richard Connell, a hypothetical dystopia in which a wealthy man brings people to an island as prey in a game of sport.

Later, I’ll read a report on border enforcement agencies’ “Deadly Apprehension Methods” compiled by La Coalición de Derechos Humanos (The Coalition of Human Rights) and No More Deaths and imagine the firsthand accounts Lisa must have heard over the years. Among CBP’s detainment techniques is the “chase and scatter”: A group of migrants is buzzed with a low-flying helicopter; people run in every direction, belongings abandoned. Some are captured. Others are left alone, lost and disoriented and without supplies. I read accounts of people running till they drop, falling off cliffs, cowering in fear, crouching in cactus or barbed wire, biting back pain so as not to cry out.8

Lisa was once caught in a buzz operation. Though she knew the whirring blades weren’t as close as they sounded, a scene from a novel whose name she can’t recall, depicting a decapitation by helicopter, flashed into her mind. How did she feel? “I’m a privileged white American,” she snaps. “I was pissed off.”

Diego downed the water offered him and ate a can of Vienna sausages “like they were caviar.” The water bearers radioed the nearest CBP field office (at Diego’s request. Consent is a core aid principle; volunteers never make the call as to what people want done or not done in situations like this.) The guards were too busy to come pick Diego up.

Lisa and the others were in a bind. They couldn’t take Diego to the station. During the first Trump administration’s immigration crackdown, a friend, Scott Warren, had been one of nine activists arrested while carrying out humanitarian work. Warren had administered first aid and given water to two men from Central America, orienting them geographically when they left the shelter. The government arrested him and charged him with two felony counts of “harboring” and one count of “conspiracy to transport.” He faced a 20-year prison sentence if convicted and was acquitted only after three years and two grueling trials, the first having concluded in a hung jury.9

They also couldn’t leave Diego to wait. They were intimately familiar with the Migrant Death Maps made by Humane Borders (Fronteras Compasivas), red with dots, each marking the spot where a body was found. Ajo Copper News lists the numbers of bodies found in this small spot of the desert alone each month (say, in December 2024, 13), along with estimates on how long each had been dead (2 less than a day, 1 less than three months, 2 less than six to eight months, 8 more than six to eight months). Also listed, how many remains have been newly identified (6 individuals) and how many remain unidentified (1,578). Since the 1990s under the Clinton administration, more than 8,600 people have perished attempting to cross the U.S.-Mexico border. In Arizona, federal officials, humanitarians and local law enforcement have recovered the remains of 4,384 people.10 It’s difficult to determine how many bodies found along the 2,000-mile border between Mexico and the United States are identified; various sources estimate some 65 percent.

It wasn’t always this way, the dying, that is. Until the ’90s, many people seeking safety for themselves and their families came to the border via large, busy ports, where aid was available. Then in 1994, the Clinton administration rolled out “Prevention by Deterrence,” a policy whose theory (make people suffer so badly they’ll stop trying to come) has driven border control ever since—despite it being an unquestionable failure.

Deaths tripled immediately. A Human Rights Watch report attributes to “Deterrence” more than 100,000 deaths as of 2023. Multiple sources suggest numbers could easily be tripled to account for remoteness, the elements, and animals. A single center alone, the Colibrí Center for Human Rights, had received reports as of 2023 of more than 37,000 missing family members, filed by people, both in the north and in the south, who will never stop looking for their loved ones.11

I think about the additional $157 billion we in the United States are about to spend on new ways to prevent people from migrating here in search of safety and security; on more efficient and no doubt crueler measures of finding, detaining, imprisoning, and deporting them; on enhanced methods of ripping apart families. Along with the $46.5 billion to complete the border wall, there are $5 billion for Customs and Border Protection facilities and $10 billion for “border security initiatives.” Add to that $45 billion for detention centers (265-percent increase from ICE’s fiscal year 2024) and close to $30 billion to hire more US Customs and Immigration Enforcement (ICE) personnel, making ICE the largest federal law enforcement agency, plus $14 billion for deportation operations, $3 billion to the Justice Department for immigration-related activities, and $3.5 billion going to state and local governments as reimbursement for immigration-related enforcement and detention costs.12

I think of all the ways $157 billion could be spent to improve people’s lives. I think about parallel truths—welcome and spurn, beauty and harshness, calm and chaos, north and south—and about all the lies many of us in the United States have believed / still believe about our country’s immigration policies and/or about those who migrate / have migrated here. I think about Lucia and Juan, who we met last week, and Elena and Carmen, who we’ll meet next week. I think about my great-grandfather, who came to the United States by boat from Sicily, and my great-grandmother, who migrated from Odessa. And I think about Diego.

When Lisa and the others radioed CBP a second time and received special allowance to drive Diego to the field office, they let out a collective sigh of relief. There, they explained to the agents his condition and urged them to get him immediate medical intervention. Lisa can only hope that happened. I imagine her resting her hand on her heart as she confides that sometimes, when his image crosses her mind, she can’t stop thinking about what they would have done if permission hadn’t been granted.

Lisa sends me updates and bits of news from time to time. Recently, she sent a link to a Tucson Sentinel article describing a water drop two weeks ago. Just after the summer solstice, two dozen No Más Muertes (No More Deaths) volunteers marked the season known for migrant deaths by distributing 364 one-gallon water bottles along a stretch of the Altar Valley, some 33 miles southwest of Tucson. They left signs, too, with messages like “No están solas” (You’re not alone). The organization, one organizer reports, dotted known migration routes with 13,096 gallons of water last year. The article’s description of the bottles as beads on a rosary chain sticks in my heart.13 I keep thinking of what it would mean to find those beads, of the splash in an ocean that is my gratitude for those who leave them, my respect and hope for those who find them.

Thank you for reading and liking and commenting. Please share or, if you’re on Substack, restack “Sharks Mouth II: Two Truths and So Many Lies.”

I would love to spread the stories of Lisa, Lucia, Juan, Diego, and the others far and wide. Next week, we’ll wrap this series up by meeting “Elena” and “Carmen” and their families, looking at a parallel history of welcome and spurn, and touching on human migration broadly.

For the comments, have you ever spent time in a desert? Were you, like me, surprised when you first saw photos of the US/Mexico border wall? Has there been a time when you needed shelter or welcome and someone provided it?

Thank you to new (and all) paid subscribers and patrons (founders). Your support helps keep this desk, now in the heart of a somewhat troubled beast called Vivian, rolling. In coming months, I hope to roll toward the US/Mexico border and elsewhere to learn and share more of these stories up close and personal.

All of this is a labor of love. But it’s not free. Your support helps keep gas in the tanks, mine and Vivian’s.

And for however you subscribe, thank you for being here. I am truly deeply grateful for you all.

Join in. Read weekly. Become a paid subscriber or patron (founding subscriber). Keep this desk rolling to where the stories are.

Juliana Kim, “How Trump's tax cut and policy bill aims to 'supercharge' immigration enforcement,” NPR, July 3, 2025.

National Park Service, “Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument Arizona.”

Paulina Villegas, Rocío Gallegos, and James Wagner, ) “‘I Feel Rage, I Feel Sadness.’ With Border Closed, Migrants Face Few Options,” NY Times, January 21, 2025.

Jeremy Duda, “Unclear how long before border crossing at Lukeville is reopened,” Axios Phoenix, December 5, 2025.

Associated Press, “Arizona port of entry to close due to huge numbers of asylum seekers, say officials,” The Guardian, December 2, 2023,

Kim, “‘Supercharge.’”

John Dougherty, “One Nation, Under Fire,” High Country News, February 19, 2007, “No Wall,” Official Website of the

Tohono O’odham Nation; Francis Causey, director, There's No O'odham Word for Wall, short documentary, 2017.

La Coalición de Derechos Humanos and No More Deaths, “Part 1: Deadly Apprehension Methods,” Disappeared: How US Border Enforcement Agencies Are Fueling a Missing Persons Crisis, last accessed July 5, 2025; National Geographic Channel, Border Wars, season 2, episode 4 “Lost in a River.”

Associated Press, “Arizona activist who gave migrants humanitarian aid acquitted in second trial,” The Guardian, November 20, 2019;

Humane Borders (Fronteras Compasivas, “Migrant Death Mapping” (death maps); Paul Ingram, “Advocates begin Migrant Trail to 'bear witness' to deaths along U.S.-Mexico border,” Tucson Sentinel, May 28, 2025 (8,600 deaths); Humane Borders, “Water for All,” (4,389 in Arizona as of June 2025).

Human Rights Watch, “Statement of Human Rights Watch: The Human Cost of Harsh US Immigration Deterrence Policies Before the US House Homeland Security Committee,” July 26, 2003.

Kim, “‘Supercharge.’”; Joseph Stepansky, “How Donald Trump’s spending bill could kick US deportations into overdrive,” Al Jazeera, July 4, 2025 (increase); April Rubin, “How the GOP spending bill will fund immigration enforcement,” Axios, July 3, 2025 (ICE as largest agency).

Adrian O'Farrill & Paul Ingram, “Just after the longest day of the year, No More Deaths leaves hundreds of gallons of water in Az desert,” Tucson Sentinel, June 24, 2025.

Holly, What an exceptional piece detailing the intensity of the crossing for any attempting it, the heartache, the waiting, the now abandoned asylum seekers, and the monetary burden to the US (that $157 billion is only the start) to chase the immigration 'terror' myth. All so very scary. Sounds like a police state is coming. Thank you for your work on compiling this important information.

Holly! This is heart-wrenching. Being on the other side of the world my understanding of what’s going on at the US Mexico border is limited. But your poignant powerful words not only made things so much clearer for me, but you also made me feel it. And fuck is it sad and infuriating.

It is also a testament to your writing skills that you can talk about such a difficult subject and still paint it so beautifully. :)