Luis Remembers.

Luis remembers taking a class on how to debone a turkey. A French woman taught the class, and two women sat behind him—one who’d left Santa Barbara and the other who’d stayed.

“God, Oklahoma?” the one who'd stayed said. “How could you even find anyone you'd want to hang out with there?”

“It wasn’t just Oklahoma,” her friend told her. Her husband had a job that had kept them moving. “And everywhere you go,” she said, “you find people just like you.”

Luis remembers traveling back with his mom to Nayarit, the town where she grew up. He loved the trips because she'd start telling stories when they embarked on the journey and stop when they arrived. She didn’t have an education, didn’t read, but she had a tremendous vocabulary. That was the way it was with women of her generation. The men, who worked with horses, didn't have any education either. And the words they had were powerful. They meant what they said. But they didn't have the extensive vocabulary of those women.

Luis remembers the kolo—the Serbian word for Balkan line dancing—how it caught him up and wrapped itself around him. At 85, he still dances every Wednesday. For the first time since youth, he’s finding himself watching more than dancing of late.

He taught dancing, Mexican at first because he thought he should, as it was his heritage. But he fell in love with the kolo. One day, no one showed up for the classes he taught with his partner, Dorothy. He learned the students had collectively decided, if the couple taught one more Mexican dance, they were walking out. They had taught one more Mexican dance.

When he was just a kid—a preteen—he’d go to festivals. He remembers two sounds. Early on, this old man would kill a pig in a way that would make the pig squeal and squeal. And some time later, Kristina Naranja would start to sing. He can still hear her voice. And everyone knew that, when Kristina started to sing, the dancing would start soon. They’d all rush to the square.

One year, he asked his older brother’s girlfriend to dance. He thought he'd have some rapport with her. “She looked at me—looked down,” he recalls, “and said, ‘You only come up to my knees.’”

Luis remembers the barn he stayed in with forty or so other fruit pickers up near San Luis Obispo—families and singles. When everyone slept on the floor together, you didn’t need a lot of room to sleep forty people. He’d go for the picking seasons with the family of his friend Raul. His mother went along one year.

A family or various groups would have rows assigned to them. Luis and Raul had a row that was just theirs. They'd get paid by the ton, so the object was to move fast. He and Raul would each work one side of the row. One side always had a little more fruit than the other. “I think it was the east side that year,” he says.

At the end of that first season, he and Raul had picked 29 tons. You were paid $2 a ton. Raul's parents told him the total. “You've got $29 coming to you,” Raul’s father said. “Now, for room and board,” he added, “you give us $30.”

Luis nearly sank into the floor. He hadn't even considered he’d have to pay for his board.

“They didn’t make me suffer long.” His eyes gleam. “They just wanted to see my face.”

“You earned this,” Raul’s father told him, handing over the $29.

One season, Kristina went with the family. She had, by then, run away with Raul's older brother. The outhouses at the barn were double-seaters, allowing two friends to go to the bathroom at once. Luis was in one of the outhouses alone one evening when he saw someone’s shadow approach. He could see through the door’s sliver that it was Kristina. The door opened inward, and Luis reached up with his leg to hold it shut. Kristina pushed from the other side.

“I'll be done soon,” Luis said, his cheeks glowing embers.

Still, she pushed. “Are you in there alone?” she asked. “Let me come in. I want to go too.”

Luis held the door shut with all his might. “Please, don’t,” he begged. “I'll be done soon.”

Later, she told him she had only been teasing.

He wished he had said something at her funeral—something about her beautiful voice. How it weaved them all together.

The Recovery of My Own Black Box

The past week, I’ve been brought to tears on freeways and trails alike. I’ll step into sunlight oozing like honey through cracks in the canopy over the gulch where I run/walk, and a whimper will escape my lips. I’ll burst with the joy to be alive and to feel it all and to be reading (listening to) the words coming through my headphones. What Looks Like Bravery by

Laurel Braitman

(who I’ve just discovered, to my pure delight, is here on Substack at Dark Horse) is, as

said of it, “happy-sad truth and beauty.” (The book came to me by way of a subscriber sans account to tag—thank you, Heather R. for being a brilliant reader with brilliant reader friends; come join us here with your own brilliant writing.)I was pulling out of a grocery store parking lot when I felt my face crinkle, and I took in a sob/breath and thought, My god, this is bravery. Yes, I’d seen the title. But I wasn’t consciously thinking of it. Rather, it was the breadth of emotional honesty and the clarity of delivery that made me whisper, “This is what bravery is.”

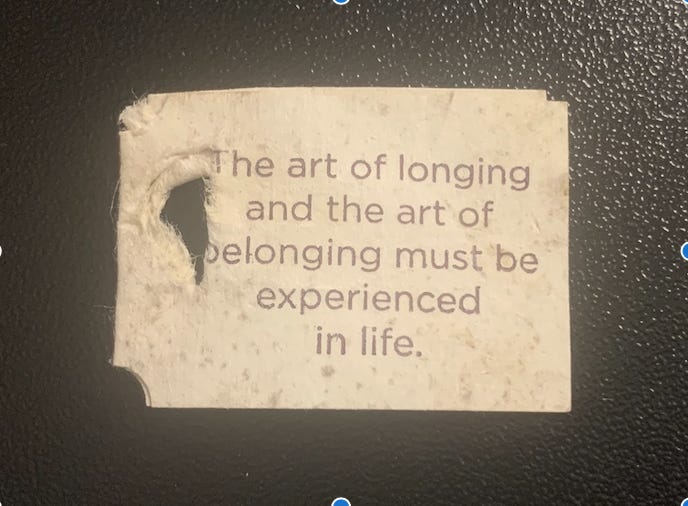

I’ve wanted to write—to be a part of the conversation in the zeitgeist making people cry on trails and see themselves and feel OK and aspire to be braver, more honest, more themselves—since I was a preteen. And while I’ve had a lovely career adjacent to those desires, as an editor of many books and writer for some dope nonprofits, I’ve shied from personal writing (or, at any rate, from sharing the writing I poured into notebooks during spotty prolific periods). I feared. Causing hurt. Bringing shame. Misunderstanding myself. Being misunderstood. Self-indulgence.

On my recent unexpected trip to my hometown, I dug through storage in my parents’ basement for the older notebooks. Only those from the past four years had been with me in the van. (While my often long bouts of nomadedness necessitate a certain minimalism, I’m fortunate to have parents with the space and tolerance to collect, like sediment layers, the deposits I’ve made before and after various walkabouts.) Surely, they’re here, I thought, trying not to panic when the first few boxes were duds. And then I saw it—a square black box tied shut with a shimmery silver ribbon like Frog and Toad’s hidden cookie box. That has to be it. I opened it. Eureka!

If nothing else, I can check facts as I write about days long past, I told myself, slipping the ribbon back in place and the box into my suitcase. In the belly of Ruby the van once more, I slid the ribbon free and dug in. Soon, Ruby’s surfaces were teeming with notebooks. There was, in fact, something else.

I was shocked to find, there among these tucked away pages, writing I dearly loved. And then I was shocked further by my shock. Like a memory, I traced the embroidered stitching along the carob leather-bound book that had accompanied me on my seven-month journey up the East Coast (launched on a northbound Greyhound). Forgotten conversations and sunrises pulled me in. I chuckled at a longing-laced letter I’d penned at Ghost Lake on the Appalachian Trail near a black bear’s den while “a cream-colored owl lifted from its perch and disappeared.” The notebook with the graph lines had been one of two in Ecuador. The one with Frida Khalo paintings and raised, sparkly gold edges had been with me in Sayulita, Mexico, and then in Santa Barbara at a place we called the Chikin Haus. I’d alternated time there in the shell of a van out back and then a tent around the corner (after losing the van bed in a pool game). The pieces in the Frida notebook are lusty, forlorn—a salty, moonlit night crescendoing with the crash of the waves, in the arms of a lover who will endlessly be gone by dawn.

Present, too, hovering around all of these books was the ghost of the way I had, often harshly, belittled these words of mine. Kept them locked away. Thought of them as silly at best. Why had I found my voice unworthy? How had I not yet come to understand that silence has long proved a far crueler weapon?

What a gift to be able to share here some of the pieces that never made it to the light of a computer screen, much less the inboxes of magazine editors or would-be agents. Today, a piece called “Luis” from a cheek-soft notebook the color of deer mushrooms. I met Luis when I first moved to Santa Barbara, returning after that Chikin Haus summer to a more permanent abode—a converted garage emerging from a bougainvillea bush that splayed atop it, draping fuchsia blossoms drunkenly down its adobe sides. The owner come dear friend had aptly dubbed it the Hobbit Hole. Luis and I first connected when he was attempting to smoke out groundhogs in his garden next door, and I went to opine. I was drawn back again and again to sit in his garden and hear his stories. I feel honored to have captured a few in this September 2010 entry.

The notebooks in the black box cover 2007 to 2014. There’s a gap, where I went silent and then turned to radio and podcasting for my creative output for a year or so. (You can find the podcasts here. Gulp.) The notebooks pick back up in 2018. There are earlier renderings I’ll go back for—another sediment layer, another excavation.

Recently, I was discussing with my daughter an essay I was thinking of sharing. “Yeah, I like it!” she encouraged. “It’ll make you feel more real.”

Girl, get out of my head! I thought. How did you know? All doe-eyed and misty, I asked, almost shyly, “Is it like that with your art, too?”

“Huh?”

She meant to readers. I’d feel more like a real person to readers.

In What Looks Like Bravery, the narrator didn’t know that ashes could look exactly like what they used to be. It occurs to me that I used to want to already be. Fully formed. Only then could I have the audacity to put my voice into the world. That restriction disappears like soot as I reach out to touch it now. Instead, I am thrilled to be becoming. To be unearthing the treasures—of writers who’ve crafted words and unearthed truths so breathtakingly my soul aches with pleasure; of the neighbors and strangers who’ve danced through my journey, among them one who told stories like a mesmerizing singing voice, drawing us to swing and swirl beneath his stage; of the eyes and mind of my younger self. That is to say, I’m thrilled to be becoming more real to myself—more and more deeply me—by sharing the journey of this becoming with you. Thank you.

Your Turn

I would love too, to hear in the comments:

What’s brought you to happy-sad tears (or just one or the other) of late?

What makes you feel more real, more like you?

What treasures have you unearthed? Any you might have long forgotten? What of yours have you been dismissive of? (How) has that changed?

Dear Holly,

It was fun to read about your friend Luis. Just bits and pieces from his life made me feel like I know him a little.

As I think of something that made me laugh and cry, I think about the recent passing of a beloved friend. As we looked through photos and memorabilia, I was reminded of wonderful times we have had together, and of her kindness and willingness to share with me her time and talents at different times in my life. It has been so fun and tender to remember, and at the same time to realize I won’t see her again for a long time and wish I could call her up and go visit and enjoy her good cooking, and admire her beautiful home and creations, and just enjoy being together.

I’m crying and smiling as I write this. Love you honey.

Holly, this is such a gorgeous piece of writing! I was struck by so much here, but particularly the idea of spending time in a career that’s adjacent to your true desires. What a gift to yourself to create this space and step fully into what you’ve wanted to do all along. ❤️